Reggie Jackson recalls racism incident: ‘I wouldn’t wish it on anybody’

Inna Zeyger

More Stories By Inna Zeyger

- Mother’s Day: How Anthony Volpe’s mom molded him into a Yankee phenom

- Michael Kay’s show heading to December ending amid uncertainty over ESPN deal

- Yankees’ Gleyber Torres projected to sign with NL West contender

- Yankees keeping tabs on Santander while Soto decision looms, says insider

- Hal Steinbrenner calls Juan Soto talks ‘good’ as Yankees weigh free agency moves

Table of Contents

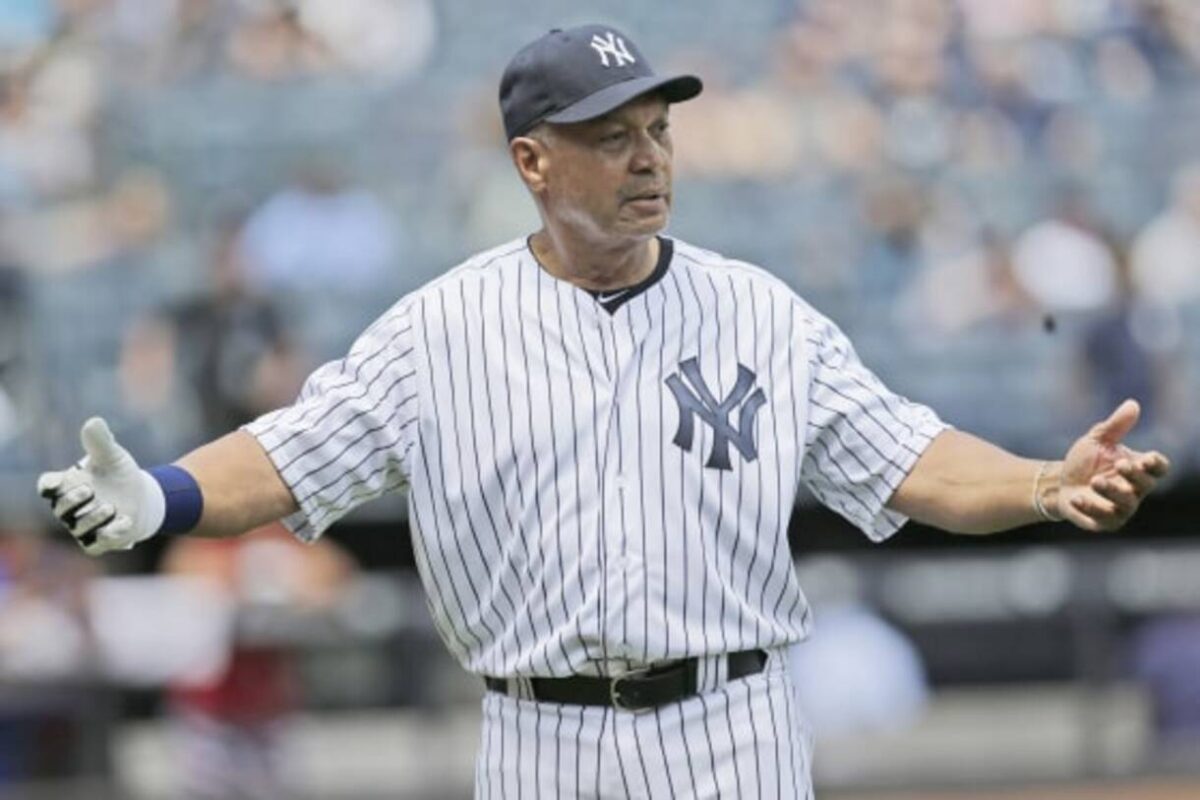

During a live national television broadcast on Thursday, Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson openly discussed his encounters with racial discrimination. The discussion was part of an event celebrating Black baseball players, held just after the Juneteenth holiday and following the recent passing of Willie Mays at age 93.

Reggie Jackson, on a panel with fellow retired stars Alex Rodriguez, David Ortiz, and Derek Jeter, shared his experiences as a minor leaguer in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1967. He reflected on the emotional toll of returning to the city where he faced significant racial challenges.

Known as “Mr. October” for his stellar World Series performances with the Oakland A’s and New York Yankees, Reggie Jackson expressed gratitude for the support of several white teammates and his manager. He credited them with standing against segregation by refusing to patronize segregated establishments and for preventing him from retaliating against racists.

Reggie Jackson’s poignant remarks included a stark reference to lynching in the South, suggesting that without his teammates’ intervention, he might have faced dire consequences for responding to racial abuse.

Reggie Jackson’s emotional attack on racism

During a Fox Sports pregame show at Rickwood Field, Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson emotionally recounted his experiences of playing minor league baseball in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1967. The event was part of MLB’s efforts to honor the history of the Negro Leagues.

He spoke about the severe racial discrimination he encountered, such as being barred from restaurants and hotels and facing threats of arson. Reggie Jackson expressed deep gratitude toward his white teammates and coaches who supported him during this difficult time, suggesting that without their aid, he might have faced violent consequences, potentially even lynching.

"Coming back here is not easy… I wouldn't wish it on anybody."

— Yahoo Sports (@YahooSports) June 21, 2024

Powerful words from Reggie Jackson on the racism he went through at Rickwood Field.

(via @MLBONFOX) pic.twitter.com/H9sXKSAfkU

Reflecting on his return to Birmingham, the Yankees legend emphasized the profound difficulty of revisiting a place filled with painful memories, stating he wouldn’t wish his experiences on anyone. When asked if he felt he had “conquered” by playing there, Reggie Jackson firmly rejected the notion, saying he would never want to relive those experiences.

“The racism when I played here, the difficulty of going through different places where we traveled. Fortunately, I had a manager and I had players on the team that helped me get through it. But I wouldn’t wish it on anybody. People said to me today, I spoke, and they said, ‘Do you think you’re a better person, do you think you won when you played here and conquered?’ I said, ‘You know, I would never want to do it again.’

He detailed specific incidents of racial discrimination, including being denied service and enduring racial slurs. He recalled a poignant moment when the entire team, led by Kansas City Athletics owner Charlie Finley, left a country club that refused Reggie Jackson entry because of his race.

“I walked into restaurants, and they would point at me and say, ‘The n** can’t eat here.’ I would go to a hotel, and they would say, ‘The n** can’t stay here.’ We went to [Kansas City Athletics owner] Charlie Finley’s country club for a welcome home dinner, and they pointed me out with the N-word: ‘He can’t come in here.’ Finley marched the whole team out. Finally, they let me in there. He said, ‘We’re going to go to the diner and eat hamburgers. We’ll go where we’re wanted.'”

Reggie Jackson’s candid revelations highlighted the pervasive racism in baseball and American society during that era. His testimony underscored the significance of MLB’s efforts to recognize and honor the history of Black players in baseball, including the often-overlooked contributions of the Negro Leagues.

Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson continued to share his poignant memories of playing in Birmingham, highlighting the vital support he received from his manager, Johnny McNamara, and teammates during his time in the minor leagues. The ex-slugger described how the team often chose takeout meals over dining at establishments that refused to serve him due to racial segregation.

“Fortunately, I had a manager in Johnny McNamara that, if I couldn’t eat in the place, nobody would eat. We’d get food to travel. If I couldn’t stay in a hotel, they’d drive to the next hotel and find a place where I could stay. Had it not been for Rollie Fingers, Johnny McNamara, Dave Duncan, Joe and Sharon Rudi, I slept on their couch three, four nights a week for about a month and a half. Finally, they were threatened that they would burn our apartment complex down unless I got out. I wouldn’t wish it on anyone.”

Reggie Jackson praised the solidarity of teammates Rollie Fingers, Dave Duncan, and Joe and Sharon Rudi, who welcomed him into their home when he was denied hotel accommodations. This arrangement, however, had to end after about six weeks when threats of arson forced him to find other lodgings.

Providing historical context, Reggie Jackson recalled that minor league baseball had been absent from Birmingham following the 1963 bombing of a church that killed four young Black girls. He noted the lack of indictments for the bombing and the positive media portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan during that period, highlighting the deep racial divisions.

“The year I came here, Bull Connor was the sheriff the year before, and they took minor-league baseball out of here because in 1963, the Klan murdered four Black girls — children 11, 12, 14 years old — at a church here and never got indicted. The Klan — Life Magazine did a story on them like they were being honored.”

Reggie Jackson expressed profound gratitude for his white teammates and manager, crediting them with helping him navigate the hostile environment. He admitted that without their support, his confrontational nature might have led to dire consequences amidst the racial tensions of the time.

“I wouldn’t wish it on anyone. At the same time, had it not been for my white friends, had it not been for a white manager, and Rudi, Fingers and Duncan, and Lee Meyers, I would never have made it. I was too physically violent. I was ready to physically fight some — I would have got killed here because I would have beat someone’s ass, and you would have saw me in an oak tree somewhere.”

Despite the adversity, Reggie Jackson’s career flourished with the Oakland A’s and New York Yankees. Known as “Mr. October” for his World Series heroics, he won five championships, was named to 14 All-Star teams, and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame on his first ballot.

Reggie Jackson’s reflections underscore the significant racial challenges Black players faced, serving as a stark reminder of the era’s social climate in baseball history.

What do you think? Leave your comment below.

- Categories: david ortiz, Reggie Jackson

- Tags: david ortiz, Reggie Jackson

Follow Us

Follow Us

As a White American, I’m embarrassed that people, even to this day, think themselves superior to other people because of the color of their skin, their ancestry, their religion, their native language, or their sexual orientation.

I judge everyone based on the axiom expressed so eloquently by MLK: on the “content of their character.”

If you use some other criteria, What’s wrong with you?

To use any other criteria betrays the fact that YOU Are The Inferior Being, not those you hate or fear.

And if you claim you’re a “good Christian” & “love Christ,” your prejudice is counter to EVERYTHING that Christ taught. So, No, you are NOT a “good Christian” and you do NOT “love Christ”; otherwise, you would “love thy neighbor as thyself,” as COMMANDED in Matthew 22:37–39.

Even as an Agnostic, I except the words of Christ & those of MLK as Truisms that are beyond human reproach.